As our cities continue to grow and expand rapidly, there has been an increasing demand for architects and craftsmen to build houses more cost-efficiently under tight deadlines. Modular architecture has been introduced as a concept which involves assembling multiple pre-fabricated modules on site to create a working unit. By joining similar elements together in various ways, modular architecture allows for more flexibilities in design and standardized repair.

Even since the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasty, Chinese timber architecture has long been known for its techniques in creating beautiful and steady joinery, which not only contributes to the ancient root of modular construction in China, but also provides useful insight to modern architects while working with different scales.

Ancient Modular Units

According to Yingzao Fashi (translated as “State Building Standards”), the oldest extant Chinese technical manual published on building construction standards, architects and builders first came up with units to measure timber as early as in 1103.

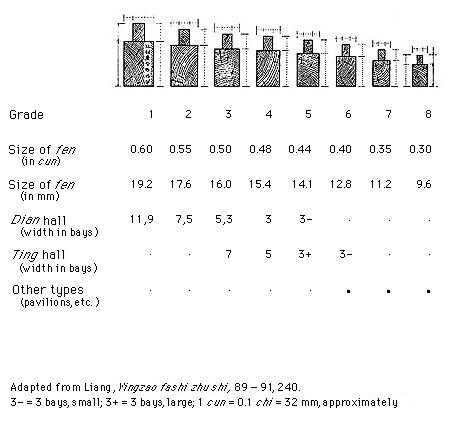

Li Jie, the author of Yingzao Fashi, served as a Superintendent of State Buildings (later Director of Palace Building) in 1100. Li first suggested to use the term “cai” as a primary unit to standardize timber materials, so that the construction cost could be more accurately calculated and the corruption in local government could be more effectively controlled. The unit “cai” was divided into 8 sizes or grades to construct Chinese timber-framing buildings of varied scales. To specify a secondary unit, each “cai” was further divided into 15 and 10 equal parts which were called “fen”. Since then, every component of a timber-framing building has to be measured by the “fen” value of the any grade of “cai”.

“Cai” was also used as a module for measurement. After ancient builders’ careful estimate of the optimal load-bearing capacity of timber, the section of each “cai” module was set with a depth to width ratio of 3:2. With this ratio, the specialist carpenters were able to cut timber materials into blocks of different scales, and assemble them freely so they became columns, roofs, and window frames. The invention of modular units greatly accelerated the construction process in the 12th century in China. Furthermore, the introduction of standardized timber regulated the scale of building based on the amount of materials used.

Chinese Order Sets

Undoubtedly, Yingzao Fashi has provided a solid foundation for the development of Chinese timber architecture, by specifying the units of measurement, design standards and construction principles with structural patterns and building elements. One of its most renowned applications can be seen in the Forbidden City’s structural element “Dougong”, a set of interlocking wooden brackets that joins pillars and columns to the frame of the roof.

Li Jie, indicated in his book Yingzao Fashi that, dougong is composed of modular wood components. During Ming and Qing Dynasty, dougong was widely utilized in the construction of imperial palaces for its remarkable structural stability to prevent earthquakes from damaging the buildings. Dougong is often found nestled beneath the eaves and roof. When the earthquake hits the building, dougong is able to transfer roof weight to the supporting columns. Moreover, because of modular design, each timber-framing building is made of hundreds of thousands of prefabricated standardized timber pieces based on geometry and logic organization, they interlock with each other without the use of nails or glue.

Therefore, with dougong, structurally the weight can be distributed more evenly throughout the building, aesthetically the harmony of symmetry and proportion can be achieved more easily as patterns can be found everywhere. Wooden components with various scales define the form of roofs, columns, windows and furniture.

Just like the Classical Order found in Western Architecture, the “Chinese Order” can be found in the design of dougong, built under the modular design strategy which outlines the basic rules of standard scales and proportion. Over the past a thousand years, ancient Chinese craftsmen used modular thinking to control the joints between roofs and columns, between furniture, between each imperial palace, and ultimately between the inside and outside of the Forbidden City.

Contemporary Application

During the 2010 World Exposition in Shanghai, the China Pavilion designed by the Chinese architect He Jingtang was constructed to showcase the spirit of traditional Chinese culture. The main structure of the pavilion involves a six-layer, 30-meter-high roof made of 56 traditional wooden brackets dougong, symbolically representing the 56 ethnic minorities of China.

During a ceremony revealing the pavilion’s design, Yang Xiong, the vice mayor of Shanghai said:

“The construction scheme for the China Pavilion contains rich elements of Chinese culture and could well display Chinese wisdom. It also has international features, modernity and could serve as a symbol. It helps develop the theme of the 2010 Expo.”

.jpg?1602636143)

Dougong was also selected for its feature of simple prefabrication and fast on-site assembly. Most pavilions at 2010 World Expo are temporary, thus the materials and construction need to be socially and environmentally sustainable. In this aspect, Dougong, with its modular design strategy, not only represents the wisdom of ancient Chinese architecture, but also meets the contemporary standards of sustainability.

In recent years, as the concept of green architecture is being promoted worldwide, more and more modular design has emerged and grown in popularity, such as the shipping container architecture. Modular design is being celebrated for its feature of shortening the construction cycle, saving construction materials, reducing energy consumption and adapting to diverse sites. Nevertheless, we should always be cautious about the changing scales and how the modules can adapt to different environments. The ancient treatise has taught us the principles on how to calculate the optimal ratio between each component. We should not be merely memorizing the numbers, instead, it is crucial for us to embed modular thinking into our contemporary construction and materials.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Human Scale. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our monthly topics here. As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

.jpg?1602636143)